While in 1894 the football landed for the first time in São Paulo, Brazil, the country was experiencing strong racial tensions caused by the promulgation of the Lei Áurea. The law signed by Princess Dona Isabella finally abolished the scourge of slavery, the one that had forever changed the history and destiny of all Latin America for the past three hundred years. Nevertheless, racial segregation, which by then was part of the centuries-old Brazilian way of life and which according to white detractors could not be erased overnight with the stroke of a pen, would continue to exist in the fazendas and also in many other sectors of society. Above all, the nascent football movement.

The moustachioed Charles Miller, the father of Brazilian football, had, as soon as he had finished his studies in Southampton, made the return journey by ship to reunite with his family in Brazil, where his father was involved in the construction of kilometres and kilometres of railway networks, the flagship of the so-called ‘coffee and milk policy’, orchestrated by São Paulo and Minas Gerais to better connect the newly-born República Velha.

The young student had landed in Brazil, bringing with him a football along with a manual of the rules of the game written in English. With the intention of importing o futebol from the land of Albion, he managed to organise the first official match in the state of São Paulo in 1895. It was played in the Italian Brás district and the gas company team and the railway company team played against each other. Twenty-two men, mostly English or Brazilians of English-speaking origin. Just like our own Charles Miller.

Blacks and half-breeds are not allowed. The order, coming from above, is to avoid dangerous cross-breeding of different races (miscigenação), especially now that Princess Isabella has freed more than three million slaves of African origin from their chains. The white ruling class, the one that financed the construction of the neo-Renaissance Amazonas Opera House, built in the middle of the Amazon rainforest (as seen in Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo), is hoping for a branqueamento, or whitening of the population by expelling, or at least expelling from society, the new freedmen with black skin.

Football adapts and resorts to a cultural clampdown. First of all, Portuguese is forbidden on the pitch. Anyone who does not master the language of Shakespeare is cut off. By regulation, English-speaking terms such as field, score, goal, half, forward, penalty and foul are used; in addition, a special rule specifies that: “in the event of a foul, the player fouled may accept an apology from the offender, provided that the apology is sincere and couched in correct English”. This means that only those belonging to the white, middle-class elite can play football. And since it is played on a Saturday, even if they wanted to, the black railway workers could not participate, because they also work non-stop that day on the construction of the estrada de ferro.

For the time being, blacks and mestizos remain watching from the sidelines. Then spontaneous challenges arise among the ruas of São Paulo where they try to imitate the new game of the whites. They try to kick anything that resembles a ball, even if the ball is made of rags and rolled-up newspaper. Thus, in a short time, football has managed to involve everyone: from the sons of entrepreneurs down to the last of the workers. The next step sees the football chains loosening on the playing field.

Sorry to call it Futebol

Creoles, mestizos and blacks gradually and timidly began to mix in the after-work teams, but the impunity with which the English hit the shins and ankles of the former slaves when they tried to get close to the ball, literally forced the latter to adapt their style of play. This is how the tilting movement that forms the basis of today’s Brazilian game was born. A defence against the white man’s violence. A kind of dance that can be traced back to samba or, better still, capoeira, that ancient martial art practised by slaves of African origin, disguised as a spectacular dance and characterised by strength, speed, balance, rhythm and lack of contact between the participants. Running, dodging and feinting. Not to die.

The history of Brazilian football is therefore inextricably linked to the dramatic racial issue. The peculiar style of Brazilian futebol brasileiro, its exceptional nature recognised globally, is a faithful mirror of the ethnic, social, cultural and historical injustices of the entire country. To ignore them is to miss the true essence of the most popular sport on the planet. That is why it is said that no people in the world have ever expressed their existence through football as Brazil has.

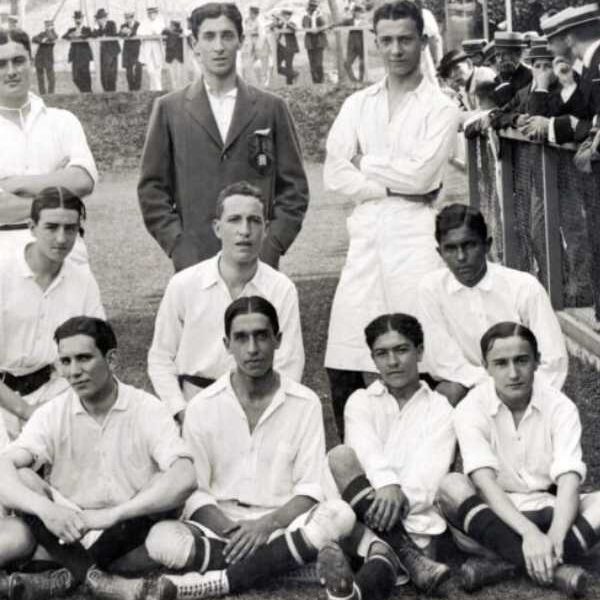

In 1910, Fluminense had a team that reflected all the ethnic groups that made up Brazil.

History of Carlos Alberto, ‘Pó de arroz’

By virtue of the ever-increasing number of railway tracks, the ball now also travels fast and easily reaches the different corners of the country. Teams with English names began to spring up everywhere, and amateur leagues and local tournaments were played everywhere. One of the most important came into being in 1906, and it is the one organised at state level in Rio de Janeiro. At the foot of the Sugarloaf Mountain, football arrived in 1902, thanks to Oscar Cox, a former student on a trip to Lausanne, who, as soon as he arrived in Brazil, founded Fluminense, a team that, due to sporting disagreements, would see some players switch to rivals Flamengo, which already existed as a rowing club.

Fluminense represents the team of the affluent Rio, a glittering and at the time predominantly bourgeois city, much like a European metropolis, built at the turn of the century in perfect Art Nouveau style. Flamengo, on the other hand, is the team of the people, supported by those citizens crammed to the limits of survival in the favelas, Brazil’s infamous and populous shantytowns, mirroring a dramatic and widespread poverty.

The inevitable rivalry between the two teams, characterised by two philosophies and two completely irreconcilable ways of living and understanding life, still tells an important cultural trait of contemporary Brazil. For over a century, every derby has literally split the city in two. Even today, during the heated encounters between the two teams, if Flu is ahead of Fla, the chorus of derision starts from the stands of the Maracanã: ‘Ela, ela, silencio na favela! No one, of course, described this historic rivalry better than Brazilian playwright Nelson Rodrigues, who once wrote: ‘in Brazil everything leads back to Fla-Flu, everything else is landscape’.

In 1914, Fluminense was in a crisis of results. After dominating the first Carioca championships, the state title had been missing from its trophy cabinet for three years. And on the occasion of the decisive match against the defending champions America Football Club, in an attempt to win the game, they send in the skilful mulatto halfback Carlos Alberto. It was the first time in the Brazilian league that a half-breed was given permission to set foot on the pitch.

In the dressing room, however, there is great concern. What will the public in the stands of the new Estádio das Laranjeiras think? At that moment, a team manager has an idea: ‘why’, he says, ‘don’t we sprinkle Carlos with rice flour to whiten his face a little?’

However bizarre, the ruse seems to be successful. At least for twenty minutes. That day, in fact, it is very hot and the high temperature is also suffered by the audience present at the stadium. There are also many ladies present, who have begun to attend football matches following the well-established custom of the city’s upper classes. They are fully dressed and even wear their inseparable white gloves. During the match, however, due to the nervousness linked to the emotions of the match, and the sun beating down on the stands, they sweat a lot and those gloves are squeezed and twisted. In the future, it will be that very gesture of twisting the lace gloves that will give Brazilian fans the nickname of ‘torcedores’, those who in the hottest moments of the match unleash the mythical ‘torcida’.

If you suffer the heat in the stands, let alone on the pitch. The fact is that at a certain point in the match, a strange buzz falls from above the stands when someone notices the cheat: o negro is playing on the pitch. The rice powder smeared on Carlos Alberto’s face has indeed started to drip along with the sweat that drips profusely from his forehead. The opposing fans notice this and start railing and insulting him heavily. That day the nickname that still distinguishes Fluminense today was born: ‘Pó de arroz’, rice dust.

Evolution of football in Brazil

Carlos Alberto, who would nevertheless finish the match unscathed and become a mainstay of Fluminense, must be considered not only the first black man to make his debut in the carioca championship, but above all as the man who changed the perception of blacks in Brazilian football forever, paving the way for future Afro-descendant champions: from Friedenreich to Leônidas, from Garrincha to Pelé, and on to Romario and Ronaldinho.

But to definitively break the chains tied around the ankles of these former slaves, now eager to play futebol freely, came first Bangu, the team born in 1904 in a Rio suburb, then Vasco da Gama, the team named after the great Portuguese explorer. It was they who were to field the first blacks in the history of Brazilian football, such as Francisco Carregal and goalkeeper Manuel Maia.

Exceptional dark-skinned champions who helped shape and develop Brazilian football around the world. Symbols of a complex mixture of dozens and dozens of peoples that produced new and different ways of playing football. In fact, with the arrival of blacks in Brazilian football, even the purpose of dribbling changed a century ago over there. It became an entertainment, an exhibition of one’s personal flair, of one’s creativity. This clear upper hand of the juggling phase even prompted some to postpone matches if they were not

This is how football in Brazil evolved. Athleticism, long throws and broadsides from one side of the pitch to the other could remain in London, along with the political and cultural models that the English wanted to impose. Space then was given to blacks and consequently to some indigenist currents that would begin to claim a more mestizo Brazil. The so-called raza cósmica and the obsessive search for the ethnic identity of the brasilianidade.

Brazil, having finally fielded both white and black players, would definitively accept its status as a mestizo people. The evolution of the Brazilian people would pass through the acceptance of Brazil’s racial diversity, which first began on a football pitch. The Brazilian people would soon turn what was perceived as a weakness – the presence of a sizeable black population – into its strength. Gilberto Freyre, one of Brazil’s leading sociologists, applied these theories to football: ‘Our football style seems to contrast with the European style in terms of qualities such as surprise, skill, intelligence, speed and, at the same time, individual brilliance and spontaneity. The Brazilians play football as if it were a dance. They are probably influenced by those ancestors who have African blood or who are predominantly African by tradition: they tend to bring everything back to dance, whether it is work or football’.

Source: GLIEROIDELCALCIO.COM

Author: Francesco Gallo